This summer, I finally followed through on a couple of experiments I’ve had nagging at the back of my head for a while:

- Seeing if I can tolerably get by on standard IMAP email hosting after 9 years on Gmail, just to know if it’s a viable alternative in some kind of hypothetical doomsday scenario

- Moving my blog – the one place where I’m not a CMS/blog developer, but a writer – from a traditional server to one of the more modern “app-as-a-hosted-service” platforms. ZekeWeeks.com is now hosted on WordPress.com Business – I’m just at the start of this experiment after a few years of “not good enough” attempts on various managed WordPress services, and will write about it later if anything interesting comes up. 🙂

Even though I was interested in seeing the current state of email outside a proprietary host, I approached that experiment with skepticism and low expectations. And I certainly didn’t expect it to turn out like it did!

Like a lot of people, I am about as averse to change in my email system as it gets. I’m the last person to complain about the latest Facebook redesign or new mobile app update, but do not mess with my email. I’ve been using Gmail for 9 years, and having all my email since high school archived and searchable feels like some kind of superpower. So I wasn’t willing to just dive into some other email system without having the ability to retreat to my reliable old setup at the first sign of trouble.

I ended up setting up some email forwarding and “from” aliases so my email routed to both Gmail and my new email system, and I could send from either one with the same email address. (I use my own domain for email, so I didn’t have any worries about people dealing with a new address).

The question of “where should I try this experiment?” didn’t take long. Before I got my shiny Gmail beta invite in 2004, I did my email through a little company called FastMail.FM. They do nothing but email, but they do it very well. Over the years, they’ve modernized their service, but in a way that isn’t motivated by launching new products or building proprietary features that break support for common email standards.

Transitioning back to FastMail for my temporary experiment was a snap. Their paid service has a generous free trial period, and they even have a well-made IMAP migrate tool with specific support for Gmail. In a matter of half an hour, all those years of Gmail archives were sitting in my new FastMail inbox.

For the following six weeks, I switched my desktop mail client to the new system, used the webmail interface a good amount, and quite a few times I completely forgot about my experiment as I kept logging back into Gmail on mental autopilot.

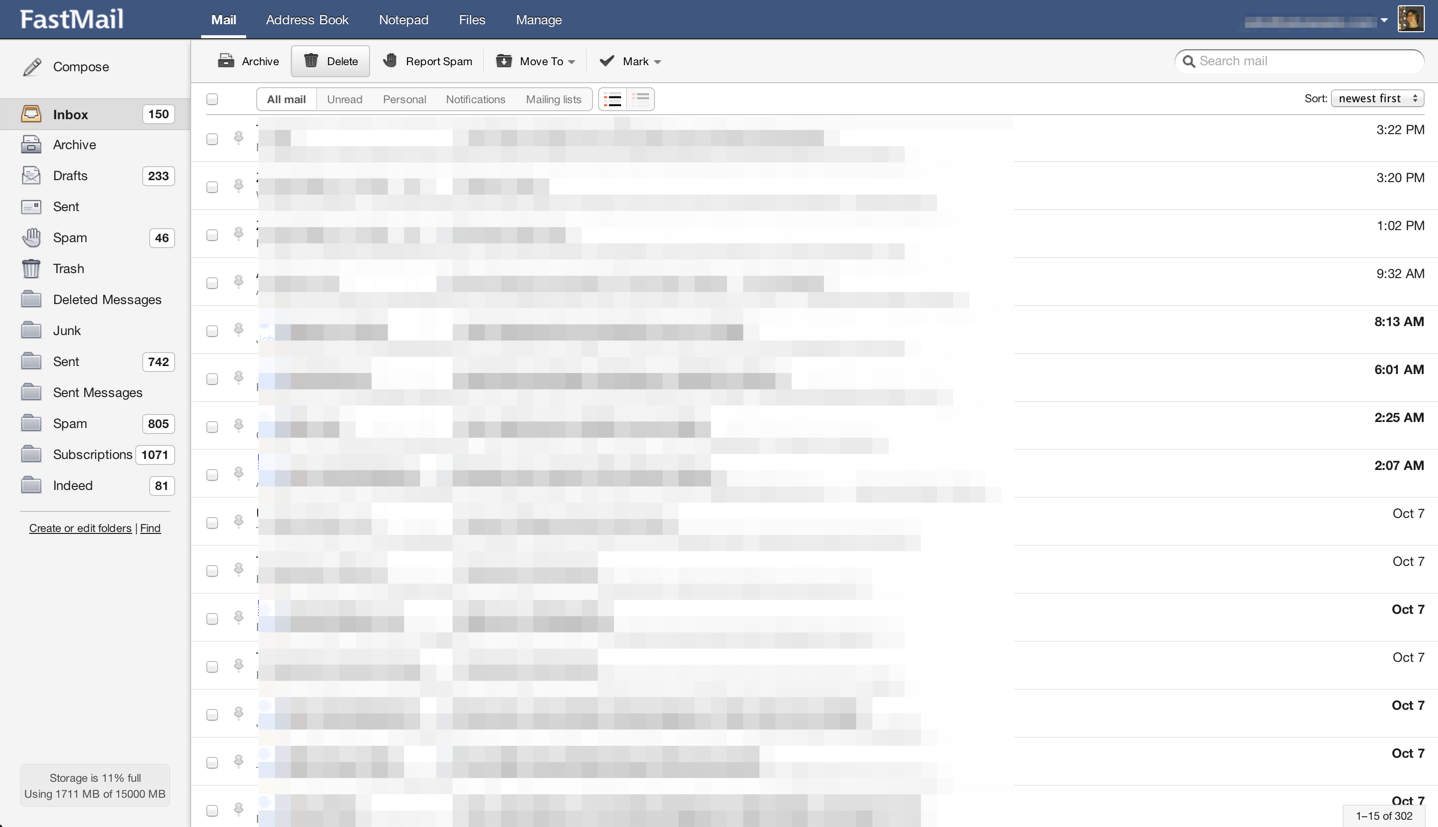

FastMail has a very nice web client that is simple but modern:

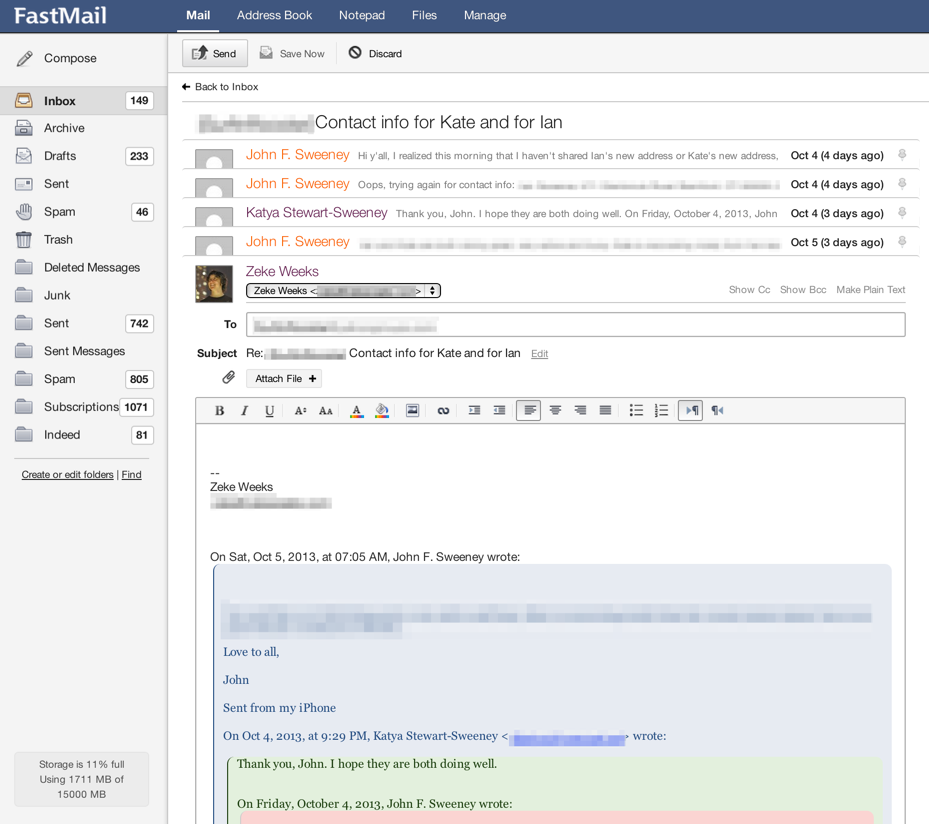

Like most other folks, they’ve taken a page from Gmail’s book and added good support for threaded messages and inline replies:

The webmail client also works great from mobile browsers. They strike a good balance of keeping the default setup simple, but offering lots of modern options to power users. (My jaw dropped when their email rules/filters interface had an option for me to program my own filter scripts!) And it’s hard to make anecdotal comparisons across services, but FastMail’s spam filtering is working just as well for me as Gmail has.

As a company, the FastMail team is small and dedicated. Since they’re paid by users, that’s the only constituency they serve. They also are quite active on their blog and community wiki – definitely not one of the services built on automating as much of the support experience as possible.

In the process of adjusting to something other than Gmail after a long time, I noticed a few things about using FastMail and standard IMAP:

Switching to standard IMAP increased my options for mail clients…

Gmail has some bits to it which are tricky to implement in a standard mail client, especially since there is no standard way to tag or archive mail. This has led to problems for people who want to use clients like Outlook or Mail.app, and has led other developers to write in specific support for Gmail’s proprietary features. (It also has some downsides for iOS users now that Google is turning off some old methods for connecting to its services.) I found myself able to try out some mail programs which are great, but weren’t an option to me while I was tied to Gmail.

…but it also showed me how email standards have some catching up to do.

It feels like most of the big web companies are in a race to monopolize as much of your content as possible. Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Facebook all offer a way to manage your email, photos, contacts, calendar, instant messaging, and files without leaving the confines of their data silo. There’s a huge upside in storing that stuff with just one account, especially when multiple different devices are involved. It’s been a joy to simply not worry about these things for the last five years or so.

The world of email with open standards is more of a “wild west” – a user has to work out many of these amenities for themselves, when they would just be provided as a convenience with a bigger proprietary host. The basic IMAP setup only syncs messages and their folders. Advanced or seriously dedicated users can get contacts and IM going through FastMail with LDAP and Jabber, respectively, but it’s anything but an “out of the box” experience. There’s also no standard support for Gmail-style tagging of messages – just the old-fashioned folder paradigm.

Even though FastMail’s main product doesn’t do as many things for its users out of the box, I think this is the only way they can possibly make an email experience this good. Trying to address so many features would steal their focus away from the core product, and require them to make a lot of compromises when it comes to their support for standards and the many applications and devices which depend on them. (There are indeed other open options for people who want everything Google Apps or Microsoft Exchange can do, such as Zimbra, but I preferred an “email only” service to the tradeoffs that come from an all-in-one open source project.)

And then there’s push email.

RANT ALERT: Unless you’re passionate about push notification standards, this section is likely to cause loss of consciousness due to extreme boredom. Skipping ahead to the conclusion is recommended for those with their sanity still intact.

To me, this is the single biggest place where standard email is lacking. Before the mobile device revolution, heavyweight business email users treasured instant email notifications on BlackBerries and Windows Mobile phones as a killer feature. When the iPhone launched, Yahoo! built a special push email system exclusive to their users. (It would be two whole years before others could get push notifications on iOS.)

Admittedly, telling an email client instantly that a new message has arrived is a particularly hard engineering challenge, especially when that device has a cellular internet connection and a battery that needs to last a long time. This is why Apple and Google have built low-level notification systems that consolidate this activity to their proprietary servers, and part of why in-house Exchange servers are expensive to operate. But none of these innovations have made their way into more generic email standards. IMAP has a half-baked solution from the 1990s called IDLE, but it requires a (battery-killing) persistent server connection, which is probably why neither iOS nor Android support it in their default mail clients. I’d say there’s a 50% chance your desktop email client supports it.

While I make this criticism on behalf of what the average user is likely to set up, I will also note that I found great IDLE support for my Android phone with the third-party K-9 Mail and Maildroid clients without noticing any impact on my battery life.

I’m not optimistic for a good push email standard soon. In theory, we could get email servers to push notifications to the most common notification services from Apple and Google, and have clients pick that up automatically when setting up a new email client. But that would require these companies to go out of their way to improve the experience for their competitor’s service, which is unlikely since there isn’t a vocal group likely to move to another platform with better support.

The End of the Experiment

After several weeks of alternating between my new FastMail setup and my still-working Gmail setup, I got an email from FastMail giving me a couple of weeks’ notice about my expiring trial. As I reflected on my experiment for a few days, I asked myself what difference I’d see in my email habits if I made a permanent switch from Gmail to FastMail. My first reaction was, “This has been a nice intellectual exercise, and I’m glad I have some very strong alternatives, but there’s no major improvement worth moving from Gmail.” I then put deactivating my FastMail trial on my to-do list.

But as I was working on something else last week, I came across a couple new posts on their blog which changed everything for me:

First, they announced that the FastMail company staff bought the company out from Opera to take it independent again. (Opera bought FastMail in 2010, with no noticeable change in the quality of the service or the people behind it.) Outside of anything else, this makes FastMail a rare gem in terms of a company which wants to do one thing, do it well, and make its customers very happy in the process.

But a week later, they announced a complete overhaul of their privacy policy, especially with respect to their approach to law enforcement surveillance and data retention as an Australian company. (This came a couple of months after they rolled out perfect forward security for their SSL connections.)

A lot of the Internet community has been rethinking their values and technical practices in light of all the recent cyber surveillance revelations, especially with Lavabit and Silent Circle intentionally shutting their own services down to protect their users’ privacy. Ultimately, email is only as secure as a postcard in both the technological and the legal sense – and no email service is going to change that. But even though I wasn’t about to move my email accounts over a security question alone, FastMail’s efforts showed me their genuine desire to build a great product that works in their customers’ best interest.

I can’t think of many other companies doing that today, so I threw my money at them and redirected my email domain to FastMail permanently. It proved itself a viable drop-in replacement for the way I do email every day, and I’m sure supporting a company like this will pay off in unexpected new ways in the long run.