Note: Skimmers should definitely skip my overtures and get straight to my recommendations at the bottom of this post.

A lot of concern has cropped up regarding “bloatware” in the most recent batch of smartphones running Android. There are really two sources of complaints in this area:

- Custom User Interface skins put on top of the stock Android OS by the manufacturer.

These skins take a generic, manufacturer-agnostic OS and create an experience unique to an individual manufacturer’s devices. Manufacturers seem to experiment endlessly with these custom UIs, often revising them with each new generation of device. They vary a lot in quality, but in turn also create more options for customers to choose the device best tailored to fit their own personal preferences. (Some will decry the existence of any custom UI, but I am in love with the time-tested HTC Sense UI, and moreover think that an “open” platform should allow for such innovations.) But it’s now impossible to buy a high-end Android phone in the United States without one of these custom UIs. With Google’s removal of their Nexus One phone from the consumer market, there are few examples of phones offering the pure “Google experience.” - Additional “bloatware” programs pre-loaded onto phones by carriers to make a quick buck.

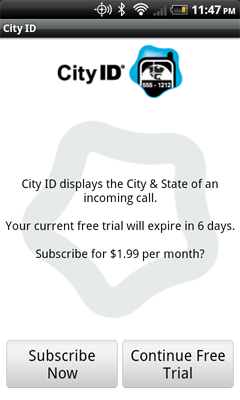

Just like many new Windows PCs, carriers now compensate for their ever-decreasing margins on device sales by loading programs onto their phones for the purpose of generating more revenue, often without regard for the quality of the customer’s experience with the end product. One phone comes with a non-removable copy of Avatar; another has the search set to Bing by default and doesn’t allow owners to change to another service; AT&T doesn’t allow the loading of programs outside the Android Marketplace; and yet others build basic caller ID or visual voicemail apps and tack disproportionate monthly fees onto the bill for their use.

I’m not surprised or discouraged to see this come up as an issue as the Android OS matures. In fact, Android works this way by design. Android would not have existed as a product if it weren’t for the support of the Open Handset Alliance, a huge consortium of carriers, manufacturers and developers who stood to benefit from such an open platform. Back in 2007, the iPhone turned the smartphone status quo upside down, and did so by taking almost all the power away from the carrier with a vertically integrated product of uniform hardware and software. Any company wishing to make money in Apple’s new market, they had to first cede the final say on all matters to Apple, who in turn prioritized the quality of the user experience above all else. In many ways, Android only became successful because it gave carriers the opportunity to re-prioritize profits over quality products and services.

This isn’t to say that Android is doomed to a future of bloatware and terrible UX. Indeed, we’re seeing rather textbook examples of differentiation in a free market. Android is the best platform for differentiating devices for different preferences and price points. And anyone who oversteps the bounds of what a customer is willing to buy, they won’t succeed. And on top of these economic norms, Android’s open nature and fast release cycle makes it the most accessible mobile OS for innovators throughout the platform, from app developers, to service providers, to device manufacturers.

But at the same time, it’s clear that no American carrier sees economic benefit in selling a “pure” Android phone. Manufacturer-controlled phones from RIM and Apple are seamless integrations of hardware and software, and even Microsoft is asserting more control over the process with Windows Phone 7. With rumors of an imminent end to the iPhone’s exclusivity, it’s possible that carriers could just see Android as a good lower-end option below “premium” offerings on other OSes.

But I think this can be easily changed to keep Android’s momentum working in a positive direction without making sacrifices to openness, profits, or much else. Here’s how:

- Change the “Google logo” terms to put the customer’s needs first again.

Android itself is totally open source and free, but you have to follow some extra rules to get the “with Google” logo and access to Google’s apps, including the Android Marketplace app store. Right now those rules aren’t very demanding, but Google could definitely insist that extra OEM/Carrier things on top of stock Android be removable by the end user. (They could even go as far as to ban custom UIs or bloatware, but I think it wouldn’t fit Android’s open nature, and would be a losing move towards competing with Apple’s business model.) “But what about the lost carrier revenue?” That’s where step #2 comes in: - Give carriers a share of Google’s 30% cut on app sales.

This gives them an incentive to make more pure “Google logo” devices over crippled alternatives. As carriers worry more and more about becoming generic service providers of wholesale data bits, this gives them a significant new revenue stream that actually rewards them for making the devices their customers really want. “But the Android Marketplace is mostly free apps, this isn’t Apple’s app store…” That’s true, but sacrifices don’t need to be made there, either: - Charge developers an annual fee for the Android Marketplace to encourage paid apps, but protect developers’ existing freedoms

Apple charges each developer $99 per year to develop and sell their applications in their store, and the only alternative is through jailbreaking. Android’s Marketplace is more financially accessible, and has a lot more free apps. To convince carriers that a Marketplace revenue share is attractive, they would need to change the Marketplace’s composure to a more revenue-driven approach. But the existing community of free app developers should also be accommodated for – I envision creating even more freedom for developers to use alternative distribution methods, first by forbidding AT&T-like restrictions on outside applications, and even – this is probably too optimistic – making root/super user access an easy opt-in setting on every phone for geeks who know what they’re doing.

I have no experience in the telecom industry, and I bet the folks in charge of Android at Google know a lot better than I, but I think something like this would be a logical direction to take as Android moves to new heights of popularity. I wonder especially about revenue sharing in the Marketplace when the carriers are going to the lengths of crippling their own devices in order to compensate for diminishing margins on unit sales.